13 Writing Lessons From “Style: Toward Clarity And Grace”

In the past ten years, I’ve read/skimmed 25 books on writing, and there’s no shortage of dumb advice. Take, for example, the wildly extolled suggestion omit needless words. This gem resides within Strunk and White’s hallowed “The Elements of Style.” It’s lovely counsel, at least in theory. But when it comes down to it, and you have one day to revise your term paper, the phrase omit needless words is as helpful as telling the captain of a sinking ship to get rid of the excess water. Yes, it’s true: you need to backspace over those superfluous characters and syllables, but how do you go about doing it? How do you know what to cut?

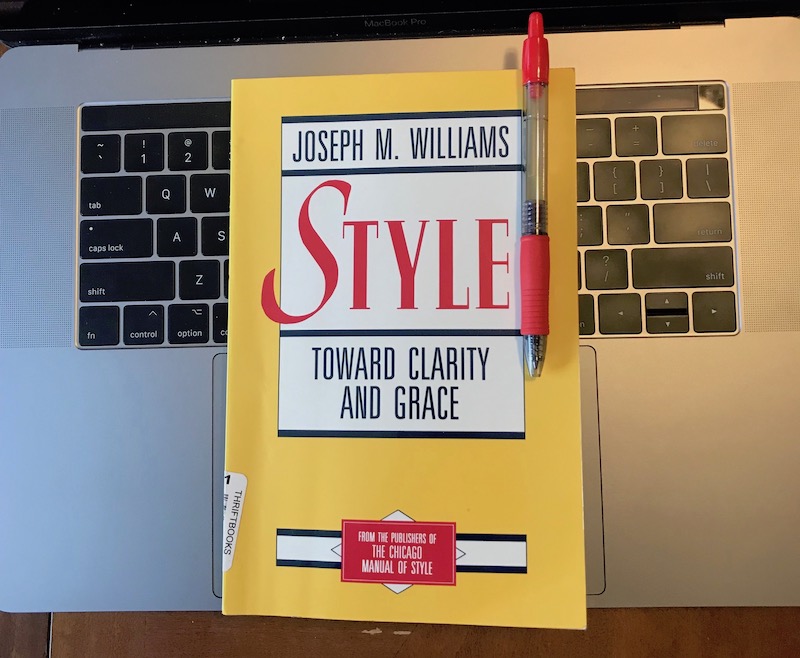

Enter Style: Toward Clarity And Grace. It focuses on what clear writing materially looks like, and avoids detours and tangents. Now, this book won’t show you how to write elegantly, though it has a chapter titled Elegance. Instead, it lays out a set of principles (with numerous examples!) that will make your writing flow and easy to understand. Best of all, it’s short: only 200 pages.

Unfortunately, this small volume costs as much as a textbook. If my college experience taught me anything, it was that short paperbacks command high prices (Amazon lists it at $47.99). And there’s a good chance that your local library won’t have a copy — mine didn’t. But I found a used copy of an older edition on Amazon, in good condition, for $11. Totally worth it.

But if you don’t want to buy yet another writing book, I’ve got you covered. Here’s my summary of the principles found within Style: Toward Clarity And Grace.

1. Avoid metadiscourse

Metadiscourse is language that describes the act or context of writing. Confusing, no? Let’s look at an example: If I were writing a persuasive piece, I might begin it with, Today, I will argue in favor of… Telling the reader that you are arguing for something is metadiscourse. Remove it and begin with your actual argument.

Similarly, I could write, Next, I will describe how…. This is also unnecessary. Just get on with the description.

Metadiscourse may include the details about the writer’s state of mind or how they came to write about this topic. But unless that information is relevant to the piece, omit it.

Just imagine I began this blog post with Today is Saturday, and, as I contemplate my latest reading of “Style: Toward Clarity And Grace,” and now that I’m situated in my office chair, with a belly full of rice and vegetables and soy sauce, and my space-heater blasting my sneaker-clad feet (I’m in the basement, after all!), as I stare at the blinking cursor in my text editor, and run my fingers through my thinning hair, I think I will begin this blog post by explaining to you, gentle reader…

Boring! Readers want you to get to the point. Skip the navel-gazing.

2. Avoid more than two nouns strung together

The book includes this example: early childhood thought disorder misdiagnosis. It’s unclear which noun is modifying which.

I made this mistake when I wrote about my first semester in college: I signed up for a five-credit Honors Chemistry class. A friend suggested I shorten it to I signed up for Honors Chemistry, and that made it better.

3. Omit what the reader can infer

Readers are smart. Don’t club them in the face, with a foam baseball bat, and explain connections they can make on their own.

For example, in my first draft, I wrote:

The book includes this example: “early childhood thought disorder misdiagnosis.” Phrases like these confuse readers. It’s unclear which noun is modifying which.

The second sentence, Phrases like these, confuse readers, is unnecessary.

4. Avoid nominalizations

You create a nominalization when you cast verbs/adverbs/adjectives as nouns, e.g., to run => runner, happy => happiness.

Take the sentence The foxes engaged in a cessation of hostilities. It has eight words and two nominalizations:

- The word cessation comes from the verb to cease

- The word hostilities comes from the adjective hostile.

The shorter version is The foxes stopped fighting. It has the same meaning with only four words. Best of all, it’s easier to parse and understand.

5. Avoid redundant categories

Don’t write, the bike was red in color.

Instead, write, the bike was red, or, the red bike.

6. Don’t hedge

Speak your mind. Everything you write is from your perspective, so there’s no need to call that out with qualifiers like in my personal opinion. Don’t be like a radio advertisement and bury your message in a sea of exceptions, exclusions, and limitations.

Trust that readers know that exceptions exist. They are reasonable souls and won’t show up at your doorstep with a torch in one hand and a list of edge cases in the other.

7. Write in the affirmative

Reword did not statements to make them simpler.

Examples

- He did not remember the time portal’s password. =>

He forgot the time portal’s password. - She didn’t arrive on time to the tarsier’s belly dancing class. =>

She was late to the tarsier’s belly dancing class.

This makes your writing tighter, and the reader will have an easier time understanding your message.

8. Avoid passive phrases

Passive phrases have the verb to be plus another verb e.g., was ambushing, were gnawing, etc. Eliminate the to be portion, and your writing will be cleaner and clearer.

Examples, with the passive portions bolded:

- I need to be working on my term paper. =>

I need to work on my term paper. - Your astronaut application must be submitted by Tuesday. =>

You must submit your astronaut application by Tuesday. - It was discovered that the hand sanitizer was hiding under the bathroom sink. =>

I found the hand sanitizer hidden under the bathroom sink.

In each case, the sentence is clearer and shorter.

9. The subject of a sentence names the cast of characters

The subject defines who performs the action and generally sits at the beginning of a sentence. A reader should be able to read a sentence once and know who the subject is.

Here’s the opening paragraph from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, by J.K. Rowling (I’ve italicized the subject).

“Harry Potter was a highly unusual boy in many ways. For one thing, he hated the summer holidays more than any other time of year. For another, he really wanted to do his homework but was forced to do it in secret, in the dead of night. And he also happened to be a wizard.”

And look at this passage from Stephen King’s Under the Dome.

“The woodchuck came bumbling along the shoulder of Route 119, headed in the direction of Chester’s Mill, although the town was still a mile and a half away and even Jim Rennie’s Used Cars was only a series of twinkling sunflashes arranged in rows at the place where the highway curved to the left. The chuck planned (so far as a woodchuck can be said to plan anything) to head back into the woods long before he got that far. But for now, the shoulder was fine. He’d come farther from his burrow than he meant to, but the sun had been warm on his back and the smells were crisp in his nose, forming rudimentary images—not quite pictures—in his brain.”

Things to notice

- The subject comes near the beginning of the sentence.

- It defines who is doing stuff.

- The sentences are easy to understand.

Also, when you specify your subject, you are less likely to write in passive voice. For example, this passive construction has an ambiguous subject: It was discovered that the hand sanitizer was hiding under the bathroom sink. The subject is it, and the reader has no idea what the antecedent (i.e., what it refers to) is. Clarifying the subject changes it to I discovered that the hand sanitizer was hiding under the bathroom sink. This revised sentence has fewer passive elements and is easier to understand.

10. The verb names the crucial actions those characters are part of

The verb follows the subject and describes what the subject is doing.

Here’s the second paragraph from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (I’ve italicized the subject and bolded the verb).

“It was nearly midnight, and he was lying on his stomach in bed, the blankets drawn right over his head like a tent, a flashlight in one hand and a large leather-bound book (A History of Magic by Bathilda Bagshot) propped open against the pillow. Harry moved the tip of his eagle-feather quill down the page, frowning as he looked for something that would help him write his essay, “Witch Burning in the Fourteenth Century Was Completely Pointless — discuss.”

And another passage from Under the Dome.

“The chuck decided he’d go a little farther anyway. Humans sometimes left behind good things to eat. He was an old fellow, and a fat fellow. He had raided many garbage cans in his time, and knew the way to the Chester’s Mill landfill as well as he knew the three tunnels of his own burrow; always good things to eat at the landfill. He waddled a complacent old fellow’s waddle, watching the human walking on the other side of the road.”

Things to notice

- The verb usually comes immediately after the subject, e.g., he was lying, Harry moved, The chuck decided, and He waddled.

- The sentences are easy to understand.

11. A sentence’s beginning should reference the sentence that came before.

Tying into the previous sentence or paragraph provides continuity. Often, a sentence’s subject will be the noun at the end of the previous sentence.

Consider this passage from Don’t Think of an Elephant! by George Lakoff (I’ve bolded the beginning of a sentence and italicized what it references in the previous sentence.)

“First, if you empathize with your child, you will provide protection. This comes into politics in many ways.”

The word This references the word protection.

Here’s the full passage:

“First, if you empathize with your child, you will provide protection. This comes into politics in many ways. What do you protect your child from? Crime and drugs, certainly. You also protect your child from cars without seat belts, from smoking, from poisonous additives in food. So progressive politics focuses on environmental protection, worker protection, consumer protection, and protection from disease. These are the things that progressives want the government to protect their citizens from.”

Linking sentences, like railcars in a train, guides the reader along from one thought to the next.

Note: There’s an exception to Avoid nominalizations: it’s OK to use them when they summarize ideas in a previous sentence. For example, look at these two sentences: On his first night, stranded on the tropical island, Sam needed to find shelter and freshwater. If these needs went unmet, he’d die. In the second sentence, the word needs is a nominalization of the verb to need and summarizes the phrase needed to find shelter and fresh water.

12. The most important word should go at the end of a sentence.

Take Victor Hugo’s quotation, He who opens a school door, closes a prison. The most important word is prison, and it comes at the end.

Another example, from the opening line from Pride and Prejudice: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” The most important word is wife.

In addition, the most critical word in a paragraph — the one that packs a punch — often comes at the end of the last sentence.

Take this passage, from Hugo’s Les Misérables.

“She was called the Lark in the neighborhood. The populace, who are fond of these figures of speech, had taken a fancy to bestow this name on this trembling, frightened, and shivering little creature, no bigger than a bird, who was awake every morning before any one else in the house or the village, and was always in the street or the fields before daybreak. Only the little lark never sang.”

That last word, sang, floods the reader with sadness and pity.

And here’s the opening paragraph from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.

“Harry Potter was a highly unusual boy in many ways. For one thing, he hated the summer holidays more than any other time of year. For another, he really wanted to do his homework but was forced to do it in secret, in the dead of night. And he also happened to be a wizard.”

The first sentence states that Harry was unusual. Those that follow show how he’s unlike other school children, culminating in the most important point: he’s a wizard.

Remember, the last word is the one the reader will remember. Make it count.

Note: There’s an exception to Avoid passive phrases: it’s ok to use a passive construction so that the most important word is last.

13. Paragraphs have two components: Issue and Discussion

The issue is the opening sentence and lays out what the paragraph is about. It begins by referencing what came before, and then introduces the topic of that paragraph. Often, the most important word — usually a noun — is last.

Sentences that follow the issue are called the discussion. They expand upon the issue, explain its finer points, and explore its caveats.

Let’s revisit this passage, from Hugo’s Les Misérables (I’ve bolded the issue):

“She was called the Lark in the neighborhood. The populace, who are fond of these figures of speech, had taken a fancy to bestow this name on this trembling, frightened, and shivering little creature, no bigger than a bird, who was awake every morning before any one else in the house or the village, and was always in the street or the fields before daybreak. Only the little lark never sang.”

In the paragraph, the issue states that the locals called Cosette, the girl in the story, the Lark. What follows is a lengthy sentence that elaborates on the issue. Though meandering, this sentence provides the reader context about Cosette and the villagers’ view of her.

Take this passage from Don’t Think of an Elephant! by George Lakoff.

“What does nurturance mean? It means three things: empathy, responsibility for yourself and others, and a commitment to do your best not just for yourself, but for your family, your community, your country, and the world. If you have a child, you have to know what every cry means. You have to know when the child is hungry, when she needs a diaper change, when she is having nightmares. And you have a responsibility—you have to take care of the child. Since you cannot take care of someone else if you are not taking care of yourself, you have to take care of yourself enough to be able to take care of the child.”

The author crafted the issue as a question, and the discussion is its answer.

Checklist

- Avoid meta-discourse

- Avoid more than two nouns strung together

- Omit what the reader can infer

- Avoid nominalizations

- Avoid redundant categories

- Don’t hedge

- Write in the affirmative

- Avoid passive phrases

- The subject of a sentence names the cast of characters

- The verb names the crucial actions those characters are part of

- A sentence’s beginning should reference the sentence that came before.

- The most important word should go at the end of a sentence.

- A good paragraph has two components: Issue and Discussion