Stop Calling People “Toxic.” (Do This Instead.)

Good morning friends!

Can I tell you something that troubles me? It’s when people label other humans as “toxic.”

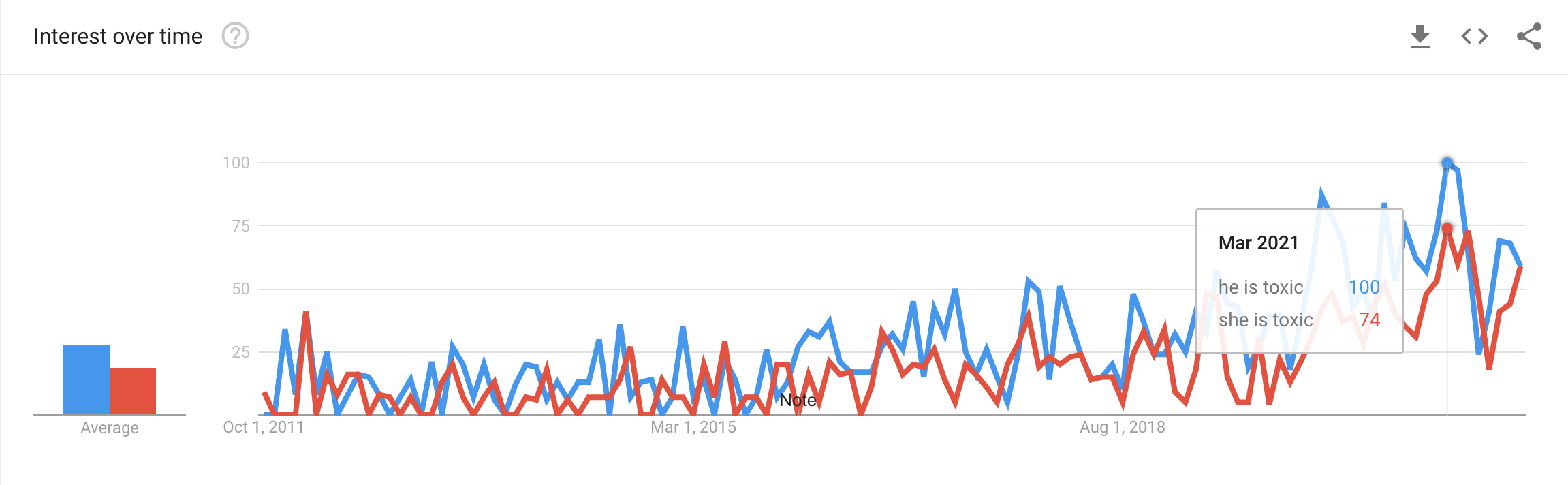

They rage, mainly on the Internet, about their “toxic friends,” “toxic family,” and how the world is just chock full of “toxic people.” Whenever someone close to them behaves unpleasantly, they publish scathing screeds, discussing how “he is toxic” or “she is toxic.” As if these unpleasant persons were a malignant ooze that will be radioactive for the next hundred millennia.

Labeling other humans as “toxic” has no basis in reality but feeds our righteous superiority. We raise ourselves up by looking down on others. And our ego eats this up!

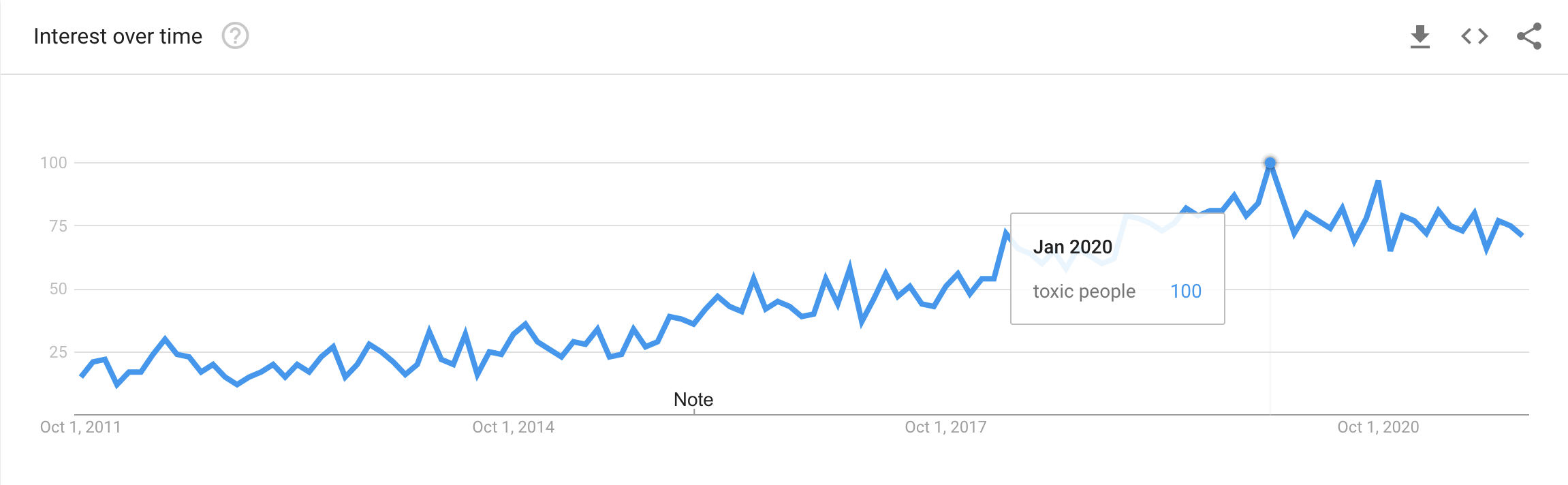

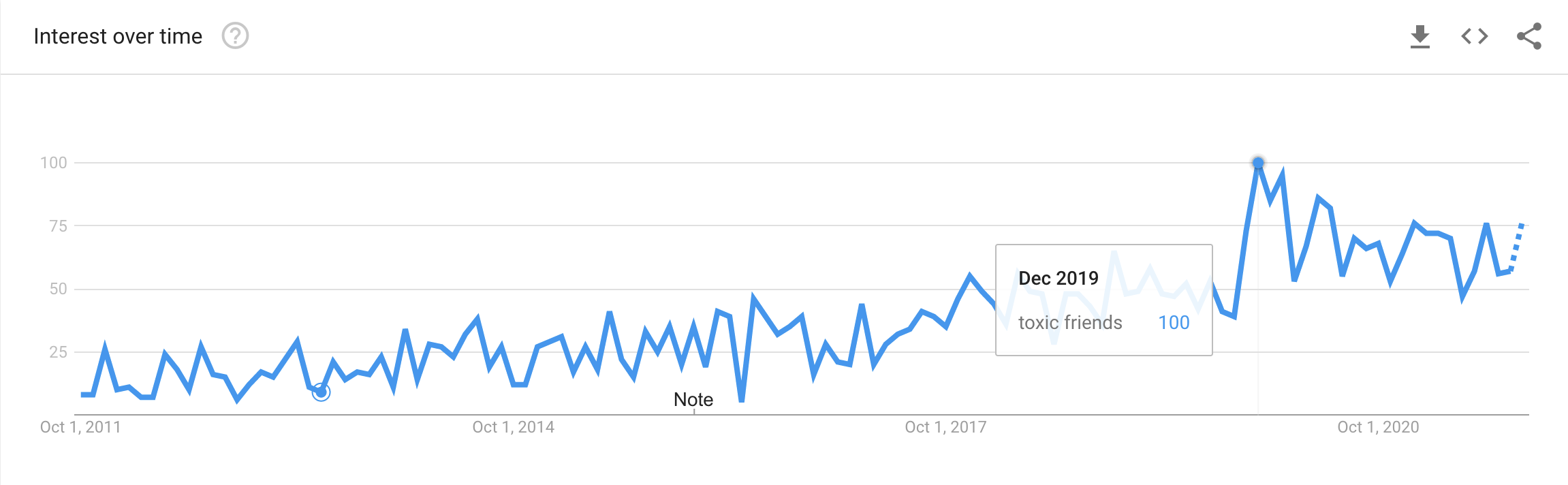

Classifying others as “toxic” is a type of performative outrage and has gained traction in the last decade. Let’s look at three examples.

1. Google searches for “toxic people”:

2. Google searches for “toxic friends”:

3. Google searches for “he is toxic” and “she is toxic”:

Using terms like “toxic” to label other humans gives us a feeling of moral superiority. We pretend like other people are inherently bad. And even subhuman. This process of “othering” gives us license to punish, and even treat these “others” like animals. After all, basic respect and human rights are only for actual humans, right? (That last sentence is extreme, but humanity has a long history of categorizing groups as subhuman and then butchering them. See Genocide.)

So I want us to stop calling people “toxic.” I want us to stop “othering” other people. Instead, let’s think of everyone, even when they misbehave, as fellow humans.

Now, this is all abstract and easier said than done. When someone irritates us or hurts us, how do we resist thinking they’re a terrible person? How do we resist assuming their character is corrupt?

I certainly don’t have all the answers, but the following mental model is incredibly helpful. It explains why people act up, and in many cases, it explains what to do about it.

The mental model

All of us have some basic needs1, including:

- Physical needs such as food, shelter, and sleep

- Emotional needs such as respect, connection, and autonomy.

When some of our needs are not met, we experience negative feelings. And these feelings trigger negative behavior. When we’re tired, hungry, or feel micromanaged, we feel grumpy or angry and react negatively to everyone around us. This is especially true when people disrespect us or threaten our safety.

Put simply: Unmet needs → bad behavior.

The way to resolve negative behavior is to resolve the unmet needs that precipitate it2. When someone is hungry and sleep-deprived, they’ll be cranky. And the only remedy is food and rest. Telling them to stop being irritable, or worse, calling them “toxic,” won’t improve the situation.

Not excusing bad behavior

This mental model is not an excuse for misbehavior. When someone hurts you, it doesn’t matter which of their needs were unmet. The harm they inflict is independent of what’s going on with their personal lives. Insulting words still sting. Punches still break bones. Or worse.

In addition, this mental model is not an invitation to surrender to abuse. You must fight mistreatment, seek protection, or run away. (Yes, running away is sometimes the best course.) There is no virtue in needless suffering. There’s no virtue in being a doormat.

We all have a fundamental need for safety and autonomy. (More on autonomy later.) As such, we must call out bad behavior. We should protect ourselves against the assholes of the world while recognizing that their behavior is a symptom of unmet needs.

Specifically, when a stranger threatens you online and violates your need for safety, you must protect yourself. Your need for safety trumps the stranger’s unmet needs. Furthermore, you have no obligation to understand the specifics of their unmet needs. And you certainly have no obligation to meet the needs of people who threaten you.

At the same time, we can’t force others to mend their ways. We can’t mandate change. Bad behavior persists until unmet needs are resolved. The only things we control are our responses and whom we spend time with.

Example 1: Jean Valjean

Let’s start with something straightforward. In Les Misérables, Jean Valjean is the protagonist and supports his sister and her seven children. But Jean can’t find work.

From the book:

It was a sad group, which misery was grasping and closing upon, little by little. There was a very severe winter; Jean had no work, the family had no bread; literally, no bread, and seven children.

In desperation, Valjean breaks a window and steals a loaf of bread from a baker. Then police arrest and haul him off to prison.

Valjean’s family needed food which drove him to steal. Pretty simple, right? People resort to crime to feed their families. The book even states this explicitly, “in London starvation is the immediate cause of four thefts out of five.”

Now, I can imagine talking to Jean Valjean and explaining why it’s wrong to steal. (We all learned this back in kindergarten, right?) In my mind, I can hear Valjean agreeing with me, even repeating my words back to me. And yet, he would steal again so long as he had starving family members. (Seriously, who wouldn’t?)

The only way to stop Valjean’s stealing is to feed his family, or at the very least, give him an opportunity to earn money to buy bread. And this situation is reminiscent of that old line about how we “first make thieves and then punish them3.”

Unmet physical needs drive bad behavior.

Example 2: Michael Scott

And unmet needs could be emotional, too. In The Office (2005), Michael Scott lacks connection and closeness. So he constantly tries to be the center of attention and be the “funny guy.” As a result, he tramples boundaries and abuses power, like when he thinks it would be funny to pretend to fire subordinates. (Can you imagine having a boss like that?)

Our instinct is to call out inappropriate behavior and tell people like Michael to stop. But they don’t change until their unmet needs are resolved. We might encourage them to have more empathy for others, but their pain drowns out any empathy they might feel. In Michael’s case, that pain is loneliness, insecurity, and the hopelessness he masks with humor. And his behavior won’t improve until the unmet needs are resolved.

Unmet emotional needs drive bad behavior.

A common unmet need: Autonomy

The proverb warns that, ‘You should not bite the hand that feeds you.’ But maybe you should, if it prevents you from feeding yourself.

— Thomas Szasz

If you’ve been an adult for more than two minutes, you’ve endured the needless nagging of a micromanaging boss. They love to tell you what to do and precisely how to do it. “I need that TPS report by noon. That’s in 37 minutes, in case you don’t know how to tell time. Now, lemme help you type on this thing we call a ‘keyboard.’ First, let’s find the letter ‘A’…”

No one wants to be treated like they’re mentally deficient. No one wants to be told how to manage their life.

Instead, we crave autonomy. We want complete decision-making power over our bodies, our work responsibilities, and our obligations. This part is obvious.

The not-so-obvious part is our desire to solve our own problems, in our own way and on our own timeframe. We want other people to see us as fully functioning adults, capable of managing our own affairs. As such, we bristle when people tell us we’re broken and when they dole out unsolicited advice.

In addition, we want the freedom to love (and marry) whomever we wish with minimal restrictions4. (Seriously, I don’t want unreasonable restrictions on whom I marry. So how can I restrict this for others?)

When someone restricts our autonomy, it feels like a boot on our neck. We get angry, and we might even lash out. Independence and self-determination are crucial for our emotional well-being.

So we must protect and safeguard autonomy for all humans. Specifically:

- Protect your personal autonomy. Push back on people who dictate how to live.

- Respect others’ autonomy. Don’t interfere with others’ decisions, so long as they don’t hurt anyone.

- Fight for political reforms that maximize autonomy for everyone.

How I view other people (well, try to)

I try to see other people as thoughtful and well-intentioned. I try to assume that they bear me no ill will. And when they behave badly, I try to look past their actions and guess what unmet need they have. My mother-in-law is a master of this. Whenever someone is grumpy, she’ll ask, “Are you having a rough day?”

Another example of this is found in Eitan Hersh’s book Politics Is for Power. The author discusses how bad drivers make him irate, which is the opposite of his brother-in-law’s reaction:

If I’m driving down the highway, my three kids strapped into car seats in the back of our minivan, and I see a car swerving in and out of lanes, accelerating past me at ninety miles an hour, I get upset. I tense up, clutch the steering wheel. Maybe I’ll blurt out something just barely left of R-rated, mindful of the children. I honk an extended honk into the expanding distance between the speeding driver and my minivan to demonstrate how annoyed I am.

But do you know what my brother-in-law does in this situation, when he sees someone speed past him? He thinks to himself, or maybe he says to those in the car with him with a smile, “Driving that fast, I bet that guy really needs to use the bathroom.”

Viewing bad behavior as a result of unmet needs (and not a product of criminal negligence, malicious intent, or corrupt character) has made me more compassionate. I’m more willing to listen to others’ plights and more patient with infractions of social etiquette.

One positive byproduct is that I sidestep the majority of negativity cycles. Instead of responding negatively to bad behavior (which escalates into an argument), I ignore it. I let it pass by and fade away. As a result, I spend far less time arguing and debating with the people around me. I spend less time feeling hurt and angry. And life is so much smoother.

Now, critics say that a portion of society is not well-intentioned but rather malicious. And they’re not wrong. A few people are malicious, and an even greater number are absolutely oblivious. But it’s entirely reasonable to take a charitable view of bad behavior while distancing yourself from these people. It’s perfectly reasonable to see Michael Scott, to see his unmet needs, and to keep your distance.

It’s also helpful to turn the tables. When I act out and misbehave, I’d prefer people to see this due to unmet needs instead of calling me “toxic.” I want people to take a charitable view of me, so I (try to) take a charitable view of them.

This mental model applied to parenting

As a parent, I want to limit the tantrums and meltdowns my kids have. It’s embarrassing to have your child throw a screaming fit in the check-out aisle of the grocery store! And while I want to avoid all forms of embarrassment, I also want my tiny humans to feel good and be happy. I want them to grow into well-adapted adults that can make the world a better place.

So when my kiddos act up, I do my best to see beyond the behavior, beyond tears and tempers, and see what their unmet needs are. I’ve come to realize that small children have numerous unmet needs. Even the kids of the most well-intentioned parents will spend part of their day feeling dissatisfied and disgruntled. And much of this discontent is preventable.

Now there’s not time to enumerate all unmet needs that tiny humans contend with, but I’ll briefly go through four groups or classes of needs:

1. Need for sleep and food. Kids morph into grumpy goblins when they’re tired and hungry—as do most adults! So my wife and I eat on a regular schedule and enforce regular bedtimes. (My son even calls me the “bedtime boss.”)

2. Need for fairness. Children are keenly attuned to what is fair. So the wife and I strive to treat our two kids equally. This can be difficult because our son is three years older and has more freedom (and responsibility) than his sister. But we make things as equitable as we can.

3. Need for autonomy. Kids want complete control over their decision-making. Left to their own devices, they would stay up all night playing Minecraft, gobble jelly donuts for every meal, and adopt a dozen stray dogs. None of this is reasonable, of course. We have to have bedtimes, eat the occasional vegetable, and right now, we can’t have a dog.

This is extremely disappointing to my kids, but we try to let them control as much of their life as is reasonable. Every day they have unstructured playtime, and we regularly take them to the public library and pick out books. Even at bedtime, my daughter decides what order she wants to do things like getting a drink, going to the bathroom, and getting hugs from mom and dad.

4. Need for control. Children aren’t born with any boundaries. Instead, they see people as a means to an end or an obstacle to shove aside as they bolt toward that pan of peanut butter brownies. As such, little ones experiment with ways to exert power over others and generally boss people around. So I’ve said things like, “You can’t dictate what your brother eats for breakfast.” and “You can’t force your sister to stop giving you the stink eye.”

Tackling this particular issue is difficult because there’s no middle ground. No compromise. As parents, we don’t allow our kids to control others. They can only control themselves. This is hard for kids to hear, especially when they’re tired, hungry, or lack autonomy. I mean, we have a whole bunch of adults running around society who haven’t figured out that it’s not OK to control other people.

Acknowledging that my kids have numerous needs (just like adults!) has made me a better parent. Compared to adults, little ones are far less capable of meeting their needs, so it’s incumbent upon me as their parent to help them meet their needs. Now, I’m not perfect at this, but it’s something I’m mindful of. And I think it shows: My kids are generally happy and content. And they are learning how to identify their own needs and speak up when they need something.

This mental model applied to friendship

Walking with a friend in the dark is better than walking alone in the light.

– Buddha

The Courage to Be Disliked is a series of dialogues between a philosopher and a youth. These two characters discuss how to live, set boundaries, and make society better. At one point in the book, the philosopher even states that any two people are the basic unit of society: “When there are two people, society emerges in their presence, and community emerges there too.”

I argue that friendship is the basic unit of society. Without friendship and its attendant trust and mutual aid, society would collapse. But long-lasting friendships are difficult to create and maintain as adults. Work and family obligations crowd out time that could be spent with friends. In addition, we don’t always have all of the necessary skills to maintain friendships. Too often, we don’t do enough to join us together and do too many things that split5 us apart.

Friendship is a precious thing, and we must preserve it. We must protect it from falling apart. In my experience, when it does fall apart, it’s always because of bad behavior that stems from unmet needs. It’s like that quote from Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Good friendships, the ones that last, are all alike in that they meet some basic needs.

Let’s look at three specific needs:

1. Need to drive conversations. People need someone to listen to them. They need to be heard. In healthy friendships, both parties take turns directing where the conversation goes and who gets attention. I call this the spotlight method where people take turns shining the spotlight on themselves.

2. Need to choose activities. Shared experiences are what build friendships. And good friends take turns selecting activities. They might even do things they’re not excited about because the relationship is more important than the activity.

3. Need for empathy and validation. Friends celebrate each other’s successes and mourn each others’ losses. “Rejoice with them that do rejoice, and weep with them that weep.6” In addition, friends validate each other’s feelings.

When friends behave badly, it’s not because they’re “toxic.” It’s because of unmet needs. They might need to be heard or need empathy and validation. Or they might just as need a turn choosing an activity.

For me personally, it’s so beneficial to view friendship through the lens of unmet needs. As a result, I’m a better listener and more willing to offer empathy and validation to my close friends. I’m more likely to celebrate their wins and commiserate their losses. Now at age 40, I have stronger friendships than I did in my 20s.

This mental model applied to being an employee

On any given day, one of the employees in your workplace will be cranky. In some cases, the crankiness stems from unmet needs in their personal life. But often, it’s a direct result of unmet needs related to their work.

Three specific needs are:

1. Need for clarity. Workers need a clear vision of what’s expected. They need to know what success looks like for their role. And they need all the necessary information to complete assignments.

2. Need for fairness. Employees need to be paid the same as others who do the same job. In addition, they need to get credit for their contributions and need respect in the workplace.

3. Need for autonomy. Workers need room to exercise creativity and experiment with novel solutions to problems. Likewise, they need to know what decisions are theirs to make.

When employees act up, it’s usually because one of these needs is not being met. I mean, I certainly get grumpy when I lack clarity, fairness, or autonomy!

So if you’re a manager, be aware of your direct reports’ needs. Check-in regularly and make sure they have clarity, fairness, and autonomy. In an ideal world, employees would tell you when one of their needs is unmet. But more often than not, employees aren’t even aware of their unmet needs. They just know something is wrong.

Parting thoughts

This mental model of unmet needs → negative behavior has been incredibly helpful in understanding how people operate. I look past labels like “toxic”—which only serves to feed my ego—and I see bad behavior as a consequence of people’s pain. (And this pain is everywhere!) As a result, I’m less likely to respond to grouchiness, and I (usually) sidestep the all-to-common cycles of negativity.

In some cases, I can help people meet their needs. Specifically, I can:

- Ensure my kids go to bed.

- Listen to my wife talk through an issue at work.

- Help a coworker work through a complicated problem.

Lastly, I respect other adults’ autonomy. I let them solve their own problems, and I don’t interfere in their lives. They have complete decision-making power over their bodies, work obligations, and personal lives. They manage their life just as I manage mine.

Take action:

When people misbehave, ask yourself what negative feelings they might have. Ask what their unmet needs are.

Examples:

- When your spouse is snippy, they might be tired or frustrated.

- When your coworker is cranky, they might be stressed out.

- When your kiddo is crabby, they might lack autonomy.

- When your boss is bad-tempered, they might be under tremendous pressure.

In fact, just assume that everyone you talk to is hurting in some way. Loneliness, a lack of autonomy, and sleep deprivation are common culprits. But people do their best to hide their pain. They put on their “happy face” and pretend that everything is fine. But everything is not OK, and sometimes people’s pain manifests as undesirable behavior.

So when that behavior pops up, pause before you react. Ask yourself what negative emotions they’re experiencing and what unmet needs they might have. Ask what small things you might do to help meet their needs. Sometimes there’s nothing you can do, and that’s OK. But just thinking through this will make you kinder and more compassionate.

And you’ll feel a lot better too.

Thanks to Diane Callahan and Thomas Weigel for reading drafts of this!

Footnotes

-

Want a longer list of needs? Check out Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Nonviolent Communication’s inventory of needs. ↩

-

I first learned about this concept in the book Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life by Marshall B. Rosenberg. ↩

-

From Utopia by Sir Thomas More. ↩

-

One reasonable restriction is ensuring that both parties can consent, e.g., they’re of legal age and sound mind. ↩

-

There’s this idea that some actions join us together, bring us closer, and there are some actions that split us apart. I originally got this idea from a book on writing called Verbalize by Damon Suede. ↩

-

King James Bible, Romans 12:15 ↩